What you’re about to read is light-hearted but it makes the serious point that the Beatles knew what to do with good luck. I’ve tried not to be silly: for example, you could say it was good luck that the five-year-old John Lennon chose his mother Julia and Liverpool over his father, Alf and New Zealand.

This story tells how good luck came the Beatles way. There was bad luck too: deaths of friends and relations, the burning of Beatles’ records, and bad vibes between Paul McCartney and Allen Klein, but that’s a different story.

There is an opportunity for feedback and we’d love to hear from you on The Beatles Story’s social media channels!

Spencer Leigh

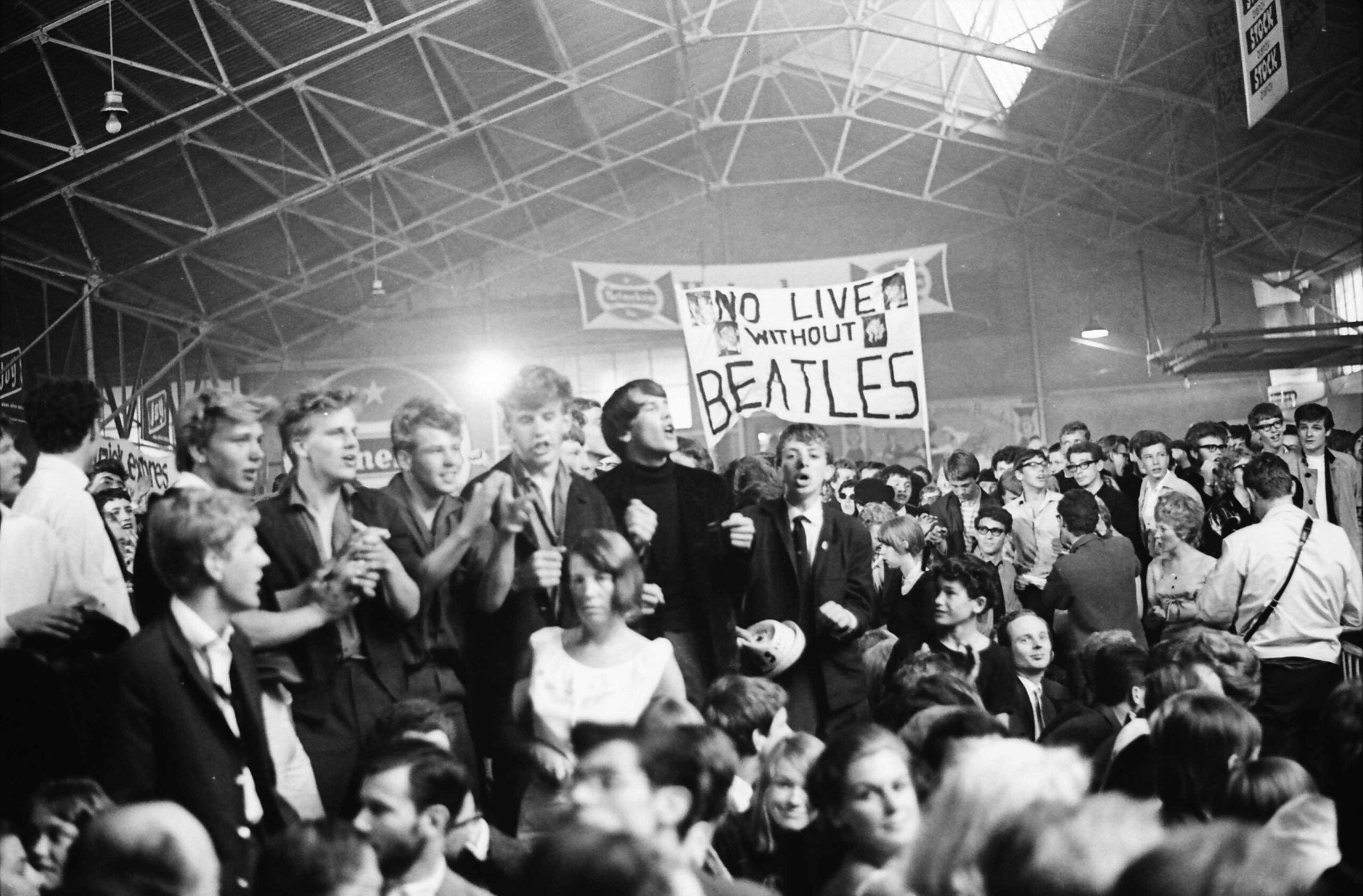

In November 1963 Marlene Dietrich came to London for the Royal Variety Performance and was astonished by the screaming fans outside the Prince of Wales Theatre. Had she gained a new following that she knew nothing about? She soon discovered they were screaming for the Beatles,

The excitement was described by the Daily Mirror as “Beatlemania”, and then in December, William Mann, the music critic of The Times, referred to their Aeolian cadences, followed by another serious critic, Wilfrid Mellors, calling Lennon and McCartney “the greatest songwriters since Schubert”. John and Paul laughed but it heralded a wider acceptance and led to the Beatles being reviewed in quality newspapers.

Unquestionably, the Beatles’ success can be attributed to their talent, their personalities, their management and their adaptability, but I would suggest that luck also played a substantial part. The Beatles had supreme good luck and perhaps more to the point, they knew what to do with it. The Beatles always seemed to be in the right place at the right time.

John, Paul, George and Ringo were all born in Liverpool in the early 1940s and were raised in a maritime city which had been heavily bombed during the War. Years of austerity followed but families secured televisions around the time of the Coronation in 1953. There were no teenage programmes. Teenagers – the term had only just been created! – aspired to be younger versions of their parents.

The youthquake came from America in the early months of 1956. Elvis Presley and Little Richard could have come from outer space as their exuberant rock’n’roll was so different from the bland ballads of the day. In the UK, Lonnie Donegan developed a frenetic form of American folk music, called skiffle.

With schoolfriends and a couple of outsiders, John Lennon formed a skiffle group, the Quarrymen, but he was edging towards rock’n’roll. In the hall at St Peter’s Church in Woolton in July 1957, Paul McCartney played John Lennon Twenty Flight Rock and he was soon a Quarryman.

With their talent and interests, John and Paul would have been involved in the growing beat scene on Merseyside in any event but that encounter set the pattern for the rest of their lives – and our lives too.

More good luck – compulsory national service was abolished in 1960 and all future Beatles sighed with relief. It would have meant living in barracks for 18 months, accepting firm discipline, and having regulation short-back-and-sides. They’d have made new friends and it is unlikely that a beat group would have reestablished itself with the same members.

One of the great marketing points about the Beatles was that they all came from Merseyside – indeed, from south Liverpool. This gave them a striking public identity which would have been different if say one of them had been born in Wigan, just 20 miles away.

Instead of being conscripted, young lads took paid employment. Soon teenagers could afford electric instruments (on hire purchase) and the latest American records and so the Merseybeat era was coming together. Buddy Holly played Liverpool Philharmonic Hall in March 1958. There was an import ban on American instruments, and the youngsters saw Holly with his Fender Stratocaster and yearned to play one.

The Quarrymen reduced to John, Paul and George, but early in 1959 George Harrison moved to the Les Stewart Quartet as bookings fell away. He returned in August for the opening of the Casbah, run by Pete Best’s mother in their family home. They added John’s friend from art college, Stuart Sutcliffe, and with a passing drummer Tommy Moore, they backed Johnny Gentle on a short tour of Scotland. Gentle praised them to his manager Larry Parnes but fortunately, Parnes didn’t follow up: it would have been too early and he would have been the wrong manager.

The Quarrymen performed in Allan Williams’ Jacaranda coffee bar. Allan and calypso singer Lord Woodbine sampled night life in Amsterdam seeking ideas for Liverpool clubs and on a whim, they moved to Hamburg. Allan heard beat music in the St Pauli district and told club owner, Bruno Koschmider that he could provide better. First, Howie Casey and the Seniors were successful and then Williams recommended the Beatles, largely because they didn’t have day jobs and were available, which was very good luck indeed.

So, in August 1960, John, Paul, George, Stu and drummer Pete Best headed for Hamburg. They played several hours a night and developed a raucous, rebellious style that German teenagers loved.

The Beatles met Tony Sheridan in Hamburg, a rock’n’roller from Norwich who had been too unruly for Larry Parnes and not accepted his discipline. He was however perfect for the wild, anything goes Reeperbahn. He taught the Beatles not to go through the motions: don’t be satisfied with bland covers of American songs. Own your time on stage and do what feels right. This made Sheridan an erratic, argumentative performer but the Beatles saw how to use this approach to their own advantage.

Stuart Sutcliffe suggested the biker look and the name ‘Beatles’, an improvement on the Quarrymen. It was a nod to Buddy Holly’s Crickets but spelling Beatles with an ‘a’ ensured a double take as fans would argue over the spelling and chuckle at its punning humour. Stu’s girlfriend, Astrid Kirchherr was the first to photograph the Beatles and her stark, black-and-white images remain classic. The Beatles radiated star quality even though at the time, they were nobodies.

Sutcliffe remained in Hamburg to study art, and when the other Beatles returned home in December 1960, they would have played Allan Williams’ new club, the Top Ten, but it burnt down in its first week. Not to worry. Bob Wooler added them to a post-Christmas dance at Litherland Town Hall for a measly £6. Other musicians (the Searchers, Kingsize Taylor and the Dominoes) as well as audience members were astonished by their raw, uninhibited rock’n’roll.

Early in 1961, the Cavern, a jazz club in the city centre, was moving towards rock’n’roll under its new owner, Ray McFall. Following Bob Wooler’s recommendation, the Beatles became his resident band and, again because they were free during the day, they played lunchtime sessions for office workers.

The Beatles now had what became the standard beat group line-up with lead guitar, rhythm guitar, bass guitar and drums. Okay, the Shadows had that first but they were largely an instrumental group, who also worked with Cliff Richard.

Bob Wooler, the DJ at the Cavern, would discuss songwriting with the Beatles and brought professionalism to their performances. Wooler would play ‘Piltdown Rides Again’ as they were about to appear. It added tension to a church hall performance – you knew that the Beatles were about to let rip. It was the Beatles’ good luck that Wooler took such a shine to them.

There were many great pop and soul songs from the early 60s that hadn’t been hits in the UK, largely through lack of publicity – Arthur Alexander’s ‘Anna’, the Isley Brothers’ ‘Twist And Shout’, Barrett Strong’s ‘Money’ and the Marvelettes’ ‘Please Mr Postman’. The Beatles brought their joie de vivre to these songs.

However, the familiar story of the Cunard Yanks can be discounted as the originals of all the Beatles’ covers had been released in the UK and were available in the well-stocked NEMS in Whitechapel, owned by Harry Epstein and managed by his son, Brian.

NEMS was only 300 yards from the Cavern. The beat groups would spend afternoons listening to records in the shops on Whitechapel, scribbling down lyrics and chords, checking out instruments in Frank Hessy’s and drinking coffee in the Kardomah. Whitechapel became the heart of Merseybeat.

In retrospect, it was lucky that the Liverpool Echo contained little editorial matter about beat music as it provided an opportunity for another art student, Bill Harry to create a biweekly magazine, Mersey Beat. The first issue sold 5,000 copies and encouraged solidarity amongst the Liverpool musicians.

Brian Epstein sold Mersey Beat in NEMS and had seen the Beatles on the cover as well as in his shop. An 18-year-old, Raymond Jones requested ‘My Bonnie’, a record that the Beatles had made in Germany accompanying Tony Sheridan, and Epstein, somewhat intrigued, ordered 25 copies.

Raymond Jones was a good-looking biker in a black leather jacket. It is plausible that Epstein thought, “If this guy likes them, they must be good.” Whatever, it was good luck. Raymond Jones kickstarted Brian Epstein’s interest in the Beatles. Epstein determined to see them, and he and his deputy manager, Alistair Taylor, attended a lunchtime session at the Cavern on 9 November 1961. That 300-yard walk is a key moment in musical history. After performing, George Harrison drawled, “And what brings Mr Epstein to the Cavern?”, little realising that Epstein had already decided to manage them.

The Beatles had fallen out with Allan Williams over commission, and he advised Epstein to have nothing to do with them: they’d cause him trouble. Fortunately, Epstein ignored the advice or at least, thought he could handle them. The ill-disciplined Lennon accepted that Epstein would find them work outside the area (first stop, Southport!) and in return, they would not smoke on stage, smarten up, and be punctual. Having Epstein as a manager was right on so many levels. He loved their music, their chemistry and their individual personalities and yes, they did conquer Southport.

Epstein knew that the Beatles needed a recording contract to propel them out of Liverpool. Because NEMS was an important retailer, Decca Records gave the Beatles an audition on New Year’s Day, 1962. Their success would have been a good start to the year, but Decca turned them down. They weren’t at their best: they were bored by a long journey in treacherous conditions, and they had to return the same way. They had also spent midnight in Trafalgar Square so possibly were hung over.

But again this was good luck. If they had gone with Decca, they wouldn’t have worked with George Martin and would have been recorded by the staid Dick Rowe or the younger Mike Smith, who admitted that he would have encouraged their bad habits.

In June 1962, the Beatles auditioned for EMI and played better, although George Martin had reservations about Pete Best’s drumming. He did not, however, demand his sacking, but he wanted to use a session drummer. But there were other issues.

The sacking of Pete Best is a mystery worthy of Agatha Christie but at its core Best’s playing wasn’t versatile enough for the developing Beatles. Bob Wooler recalled McCartney and Best staying behind after a lunchtime session with McCartney on drums showing Pete what to do. Bob thought Paul was being arrogant – after all, Pete was the drummer – but obviously Paul knew what was needed. A few weeks later Pete was replaced by Ringo, a happy-go-lucky guy who did what the Beatles wanted and had the ideal personality.

Another stroke of luck was in Brian Epstein recognising the attraction of a regional accent. Larry Parnes had told Billy Fury not to speak on stage as audiences might think him common. Flash forward a couple of years and we have Brian Epstein encouraging the Beatles to use their Scouse accents, which emphasised their natural wit.

Indeed, Epstein was keen to identify the Beatles with Liverpool. The Beatles’ first photographs with Ringo Starr were arranged through Peter Kaye’s studio. In line with Epstein’s requirements (and probably exceeding them!), the Beatles were taken to the waterfront and photographed aboard the salvage vessel, SS Salvor.

Again, more luck. There are no bad photographs of the Beatles, apart from those in Victorian bathing costumes. That may sound obvious but it’s not always the case with rock acts. Look at the Byrds or the Beach Boys and see how uncoordinated they can look, even on LP covers. The Rolling Stones were managed by Andrew Loog Oldham as the anti-Beatles – a clever marketing ploy that benefited both groups – but look again at the Stones: they were rebellious and anti-establishment, but Charlie Watts was always immaculate.

Although Epstein handled the sacking of Pete Best insensitively, he learnt from the experience. The Beatles were lucky to have Epstein as he differed from the dishonest or exploitative managers that were around. Epstein was efficient and honest and the Beatles could concentrate on their main job, that is being Beatles. They didn’t have money worries and they trusted each other.

Unknown to the Beatles and Brian Epstein in 1962, there was a power struggle at EMI which would benefit them. EMI’s big labels were HMV and Columbia, while Parlophone was a minor offshoot with Scottish music (Jimmy Shand), novelty records (Charlie Drake, Bernard Cribbins) and middle of the roaders like Matt Monro, admittedly a wonderful singer.

Norrie Paramor ran Columbia and had huge success with Shirley Bassey, Michael Holliday (from Liverpool), Helen Shapiro and Cliff Richard. George Martin was envious of Paramor’s wealth, which was partly attributable to extra income from writing B-sides under pseudonyms for his artists. In 1962 Martin shopped him to David Frost for the BBC’s satirical programme, That Was The Week That Was. Paramor was horrified to be outed, especially as he had to justify himself to EMI’s managing director, Sir Joseph Lockwood. He was sure Martin was behind it, but he couldn’t prove it.

Beatle authors often wonder why Helen Shapiro turned down Lennon and McCartney’s ‘Misery’. The answer is simple: she was produced by Norrie Paramor and there is no way he would have recorded a song from one of Martin’s acts.

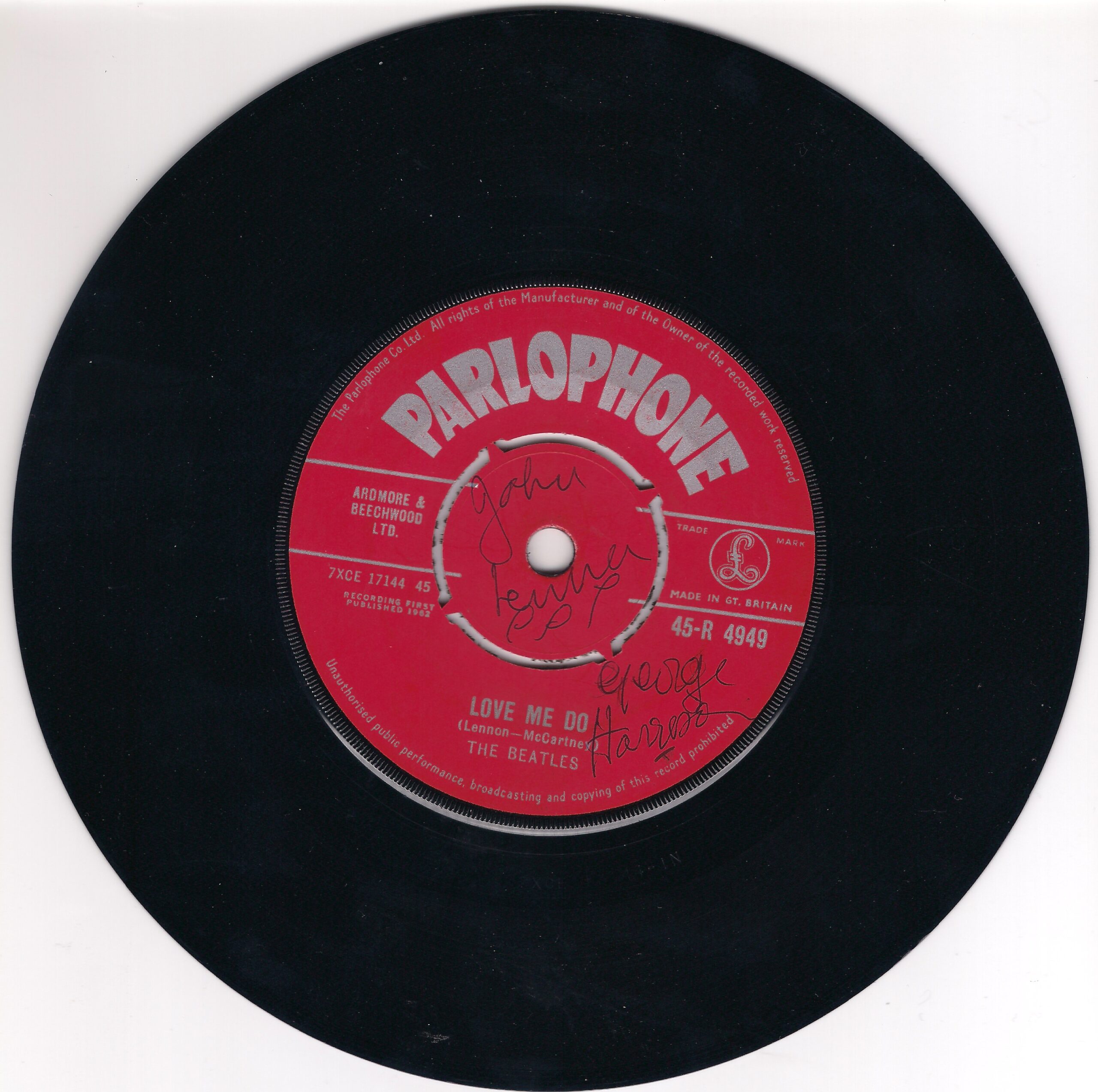

Brian Epstein was unhappy with EMI’s publishing arm, Ardmore and Beechwood as they could have done more with the Beatles’ first Parlophone single, ‘Love Me Do’. In their place, George Martin recommended his friend, the singer Dick James, with his own publishing company. James, anxious to make his mark, did a tremendous job promoting Lennon and McCartney as the UK’s best songwriters and getting other acts to record their songs.

George Martin was the perfect producer for the Beatles, able to understand their whims and wishes and make valid suggestions. He had produced the anarchic comedy of the Goons and so he knew all about crazy sound effects.

Within NEMS, Epstein assembled an excellent team, notably the press officers, Tony Barrow and Derek Taylor, ‘Mr Fix-It’, Alistair Taylor, and the road crew Mal Evans and Neil Aspinall. In a press release, Tony called the Beatles the “Fab Four”, a phrase which quickly took hold.

But not everything in the garden was rosy. There was one incident in June 1963 with the potential to derail the Beatles. The Beatles had taken a break from each other but rather than go home to his wife and baby son, John Lennon went to Spain with Brian Epstein. In my view, this was not sexual – it was power politics: John was making it clear to Epstein that the Beatles was his group and not Paul’s. When the Beatles were back together for Paul’s twenty-first in Liverpool, Bob Wooler sarcastically asked Lennon, “How was the honeymoon, John?” John beat him up and a specialist’s report, displayed in 2023 at Liverpool Central Library, showed that Bob Wooler’s nose had been broken. The incident made the national press, via Allan Williams as it happens, but it wasn’t front page news.

We don’t know what happened behind the scenes. My guess would be that the ambitious McCartney was furious with John. This thuggish behaviour went against the Beatles’ image of lovable moptops. It’s possible that Paul persuaded George and Ringo that John would have to go. Fortunately for everyone, Brian Epstein resolved the matter with John apologising and paying £300 compensation.

The differing personalities of John and Paul was their good fortune as it gave their music an edge. By and large they wrote individually and then asked each other for improvements A very good example, ironically called ‘We Can Work It Out’, perfectly puts McCartney’s verses alongside Lennon’s bridge. Note McCartney’s approach “Try to see it my way” – in other words, “I’m right, follow me”.

EMI was the leading stockholder in the US label, Capitol, but the Americans resented being under their control. EMI was happy to release Capitol product in the UK as they had Frank Sinatra, Nat ‘King’ Cole and Peggy Lee, but Capitol showed little enthusiasm for releasing British product in America. Throughout 1963, they turned down the Beatles’ UK hit singles, saying that they weren’t right for the market and anyway, they had a potentially great teenage attraction in the Beach Boys. Instead, Beatles’ tracks were licensed to Vee-Jay, Tollie and Swan, receiving little promotion and negligible sales.

By 1963 and notwithstanding the Beach Boys, American pop was in the doldrums. The rock’n’roll heroes had ceased to be relevant. Elvis Presley was making bland beach movies; Chuck Berry was in jail; and Little Richard was a minister. Buddy Holly and Eddie Cochran had died while touring. There was a wave of boy-next-door teen idols, but Roy Orbison and Del Shannon were coming through.

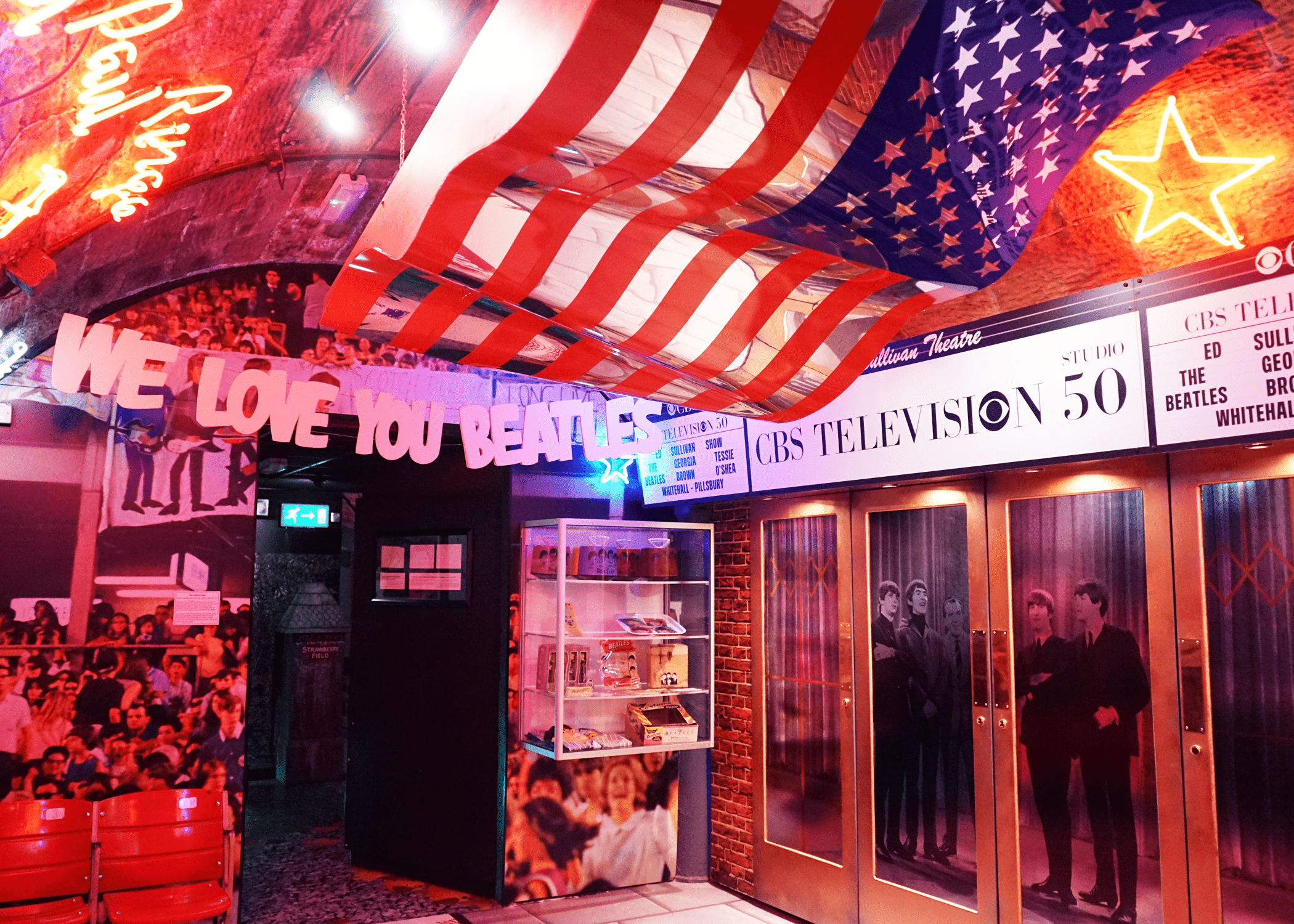

In October 1963, the American TV host Ed Sullivan happened to be at London Airport when the Beatles were arriving from Sweden. He witnessed the screaming fans and thought this could be something for his Sunday night variety show.

Brain Epstein sensed that this could be the breakthrough that the Beatles needed. British rock’n’roll artists had not fared well in America, and in particular, Cliff Richard had been humiliated as the opening act on a Frankie Avalon tour. The Beatles said they wouldn’t tour America unless they first had a major hit single.

The cards fell into place. EMI ordered Capitol to issue the Beatles’ product. A marketing budget was agreed for ‘I Want To Hold Your Hand’ with the intention of getting it to the top. The Beach Boys’ manager, Murry Wilson, was furious about all this attention being given to the Beatles and not to his own group.

Brian Epstein persuaded Ed Sullivan that the Beatles merited three appearances on the show. An American impresario Sid Bernstein, who read English newspapers and knew about the Beatles, offered them dates at Carnegie Hall and Washington Coliseum. Bernstein knew the prestigious Carnegie Hall didn’t book rock’n’roll acts but he skilfully booked the Beatles in a series which included Tony Bennett and a British singer known in America, Shirley Bassey.

As the plans were falling into place, President Kennedy was assassinated. The nation was in shock and mourning, so much so that the Singing Nun found herself at Number 1. By January 1964, the American public was desperate for something new and exciting and, as luck would have it, the Beatles had the antidote, ‘I Want To Hold Your Hand’.

It is remarkable how easily the Beatles adapted to this tsunami of fame. In the UK they had been playing theatres which might hold 3,000 fans. In 1964 they were playing US sports stadiums that held 50,000 and the move did not faze them.

The Beatles achieved international fame on the level of Sinatra and Presley, but with one big, lucky distinction. The Beatles were four individuals who could each appreciate what the others were going through and that shared experience kept them grounded.

George Martin encouraged the Beatles to be adventurous and was in his element when they made Sgt Pepper and Abbey Road, but he had been the right man from the start, even on simpler, beat group recordings. He encouraged them to pick up the tempo on ‘Please Please Me’ and suggested that ‘She Loves You’ and ‘Can’t Buy Me Love’ should open with the chorus for maximum impact. Technically, Martin knew what to do but he was also a great man manager, able to channel their whims and wishes.

Lennon and McCartney had an instinctive grasp of what made songs work and what didn’t. Willie Nelson once told me that his favourite Beatles song was ‘Yesterday’. “But” I said, “is it a great song? You don’t know what happened yesterday.” Willie said, “That’s what makes it a great song.”

When it came to films, the Beatles had a script from a Liverpool/Welsh playwright Alun Owen, noted for TV dramas, especially the socio-realism of No Trams To Lime Street. He spent time with the band and emulated their repartee. A Hard Day’s Night was directed by Richard Lester, who knew how to shoot comedy and music performances. Like George Martin, he had worked with the Goons and he encouraged the Beatles’ zaniness. Help! was more contrived but had a fine soundtrack with some sequences paving the way for pop videos.

The Beatles moved to London when it was developing into Swinging London with Carnaby Street and Kings Road and again, they never looked stupid in those fashions. Major artists (Peter Blake, Richard Hamilton) created album sleeves and they chose photographers well.

The UK voting age was still 21 and plans to reduce it to 18 were not enacted until 1969. Politicians realised it was inevitable and wanted to appeal to teenagers. The usual step would have been for the Prime Minister Harold Wilson to honour Brian Epstein for his services to British exports, but no, he awarded MBEs to the four Beatles instead.

The Beatles showed little interest in the making of Yellow Submarine until they realised that it involved some of the world’s most imaginative animators. The results were innovative, and it is regarded as groundbreaking.

The Sixties became very competitive with Bob Dylan, the Beach Boys and the Kinks plus songwriters like Carole King, Burt Bacharach and Jimmy Webb. The Beatles could match anyone, mixing mix avant-garde with commercialism and being at the forefront of new ideas.

Even the chaos of the Let It Be sessions has a magic of its own, especially now that the footage has been re-edited. The Beatles are about to break up: we know that but they don’t and it gives an added poignancy to the footage. Jean-Luc Godard made an extremely boring film about the Rolling Stones recording ‘Sympathy for the Devil’, but no one would say Let It Be was boring. There is so much to discuss as well: for example, is it a good idea to bring your partner to work?

In the early 1970s Bruce Springsteen became the ultimate stadium rocker, filling auditoriums but despite his many albums, he has not created a crossover catalogue to match the Beatles and few of his songs have become standards.

The punk and new wave era was supposedly anti-Beatles but it was a sham. Glen Matlock was sacked from the Sex Pistols for liking the Beatles but this was a publicity stunt (although he did love the band!) The Clash recorded ‘No Elvis, No Beatles, No Rolling Stones’ but they were being provocative. Punk was a variation of 60s beat but they never said so.

In 1980 when John Lennon was assassinated, Beatles tourism was in its infancy. The Cavern site was filled with rubble, with a car park at ground level. Fans left flowers there because there wasn’t anywhere obvious to put them. Tragic though it was, the aftermath created Beatles tourism. It would have happened anyway but not, I suspect, to this level. Bob Wooler referred to the new fans as “the death-watch Beatles”.

Starting in 1995 the Beatles put alternative takes and outtakes into their Anthology albums, the first volume of which sold 13m copies. It was a brilliant example of remarketing the Beatles.

The list of Number 1 hits by Liverpool artists displayed in Mathew Street has been recently expanded with the addition of the Beatles’ ‘Now And Then’, but nobody new from Liverpool had had a Number 1 for many years. The city needs new major artists so that it does not become a heritage site like Stratford-upon-Avon. I’m pinning my hopes on Jamie Webster who already has the Kop singing one of his songs.

The Beatles reaching Number 1 in 2023 shows we are dealing with something far greater than nostalgia – and that’s been very lucky for all of us.

Abba scored a remarkable success with their avatars and who knows where this will lead? The AI Beatles can’t be far behind and that will lead to another generation of fans. But despite their success, Abba will never match the Beatles.

Nor will Elton John. He has written many standards, but there is still something middle of the road and jokey about his performances: it may be unfair but to me, he looks like a man playing at being a rock star. Ed Sheeran is Elton John-lite, and can anyone imagine his songs being performed in 20 years’ time? I even have my reservations about Oasis – in my view, they took a Beatles’ B-side Rain and rewrote it – and then did that again and again.

Time can be very hard on pop acts. Look at the record collections given to charity shops. Who wants James Last, Jim Reeves, Shakin’ Stevens or even the Spice Girls today? The Beatles are immune from this. When their vinyl has been donated to charities, it is sold on ebay rather than placed in the racks with Val Doonican and Harry Secombe.

The Beatles could have fallen out of fashion, but they haven’t: they’re even in the new series of Doctor Who. The Beatles reaching Number 1 in 2023 shows we are dealing with something far greater than nostalgia – and that’s been very lucky for all of us.

Luck was certainly an important factor with the Beatles but there was also hard work, perseverance, flexibility and a whole lot of talent. The Beatles saw the opportunities and seized them, usually making the right decisions. Well done, lads.