You Know The Name: The Fascinating Story of How The Beatles Got Their Name

The story behind the naming of The Beatles has almost taken on mythical status, somewhat due to the band’s famously mischievous nature. Throughout their time as a band, they offered a mix of stories about the origin of the name, including accounts of dreams involving flaming pies, floating buns, and mysterious men visiting them on flying carpets. The reason for these fanciful explanations is likely because they found the real, much more straightforward origin of the name not ‘fab’ enough to share repeatedly.

While the story of how the band came to the name The Beatles is admittedly straightforward, their journey to embracing it was anything but. This is the story of how The Beatles got their name.

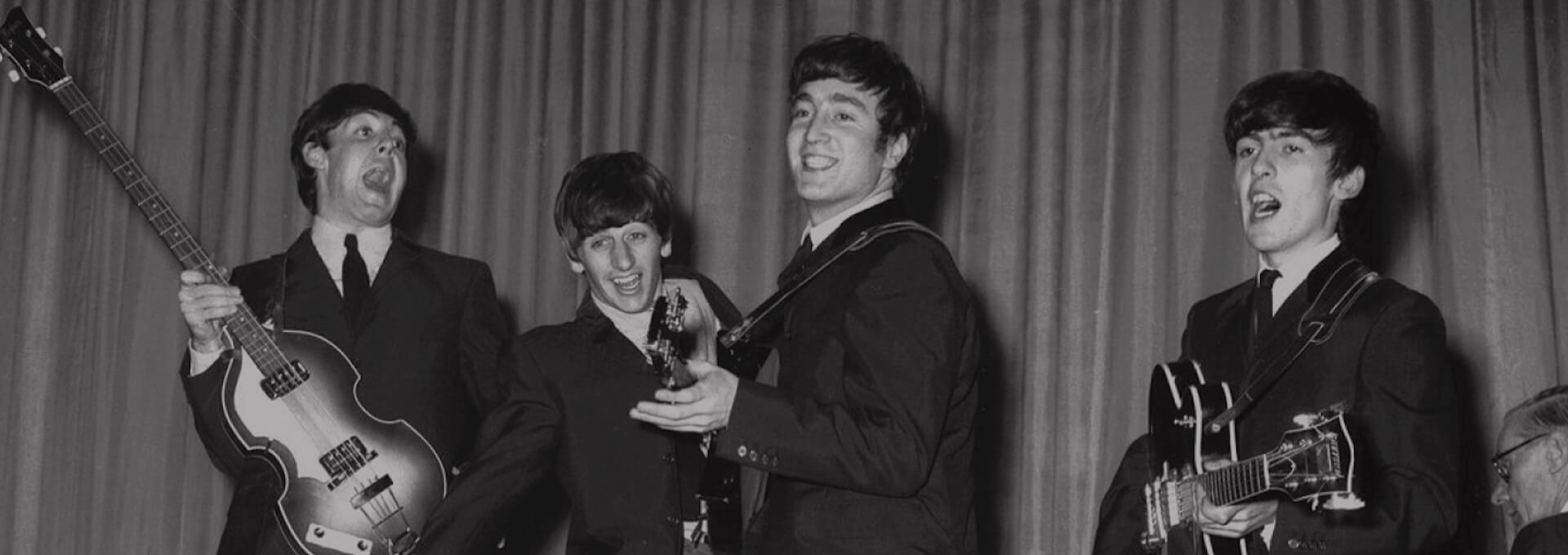

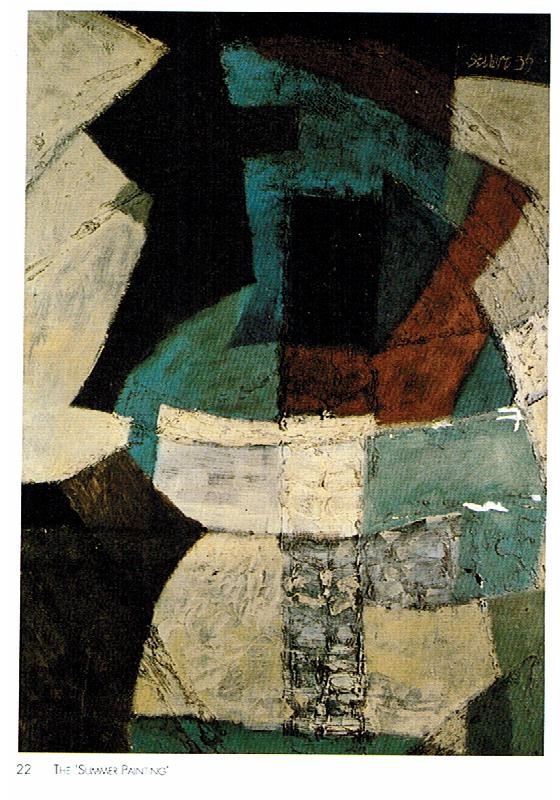

Entering 1960, the band, then a trio John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and George Harrison, was still undecided on a name, though they had recently performed as Johnny and the Moondogs. John Lennon’s friend from art school, Stuart Sutcliffe, joined the band after being convinced by his friends to invest £65—money he earned from selling a painting—into a bass guitar. The band did not have a permanent drummer; instead, they rotated through a stream of drummers, with Tommy Moore appearing most frequently.

Reprinted with kind permission from the Stuart Sutcliffe Estate.

John and Stuart came up with the name “The Beatles” during one of their late-night sessions. Unlike Paul and George, whose parents enforced bedtime routines, John and Stuart, being art students, had the liberty to stay up all night. It was on one such night that they devised the name. They brought it to the rest of the band on an April evening in 1960 while walking along Gambier Terrace by Liverpool Cathedral. Initially, Paul thought the name sounded a bit creepy, but he changed his mind after learning about its clever double meaning, seeing it as truly literary.

Use the map to see if you can find 3 Gambier Terrace, where John and Stuart lived in 1960!

John Lennon talking about how he actually came to the name The Beatles: “I was looking for a name like The Crickets that meant two things, and from crickets I got to beetles. And I changed the BEA, because ‘beetles’ didn’t mean two things on its own. When you said it, people thought of crawly things; and when you read it, it was beat music.”

After the band settled on a new name just a couple of weeks prior, the band crossed paths with Casy Jones (real name Brian Cassar) from the Liverpool group Cass and the Casanovas shortly before a crucial audition. When Casy asked what they had decided to call themselves, they told him, “The Beatles.” Cas, unimpressed, called it “rotten” and suggested it needed more syllables—something longer and more impactful, like his own band’s name. Among his suggestions were “Long John and the Pieces of Silver” and “Long John and the Silver Beetles”.

The respect the band had for Cass and the Casanovas wasn’t just professional courtesy; it was also rooted in admiration. Cass and the Casanovas had secured a spot on the bill for a Gene Vincent show, an event that had seemingly the entirety of Liverpool’s music scene in attendance, including John, Paul, George, and Stuart. This gig exemplified Cass and the Casanovas’ knack for landing impressive gigs, something they were really trying to understand.

Though John and the others weren’t too excited about Cas’s suggestions, they couldn’t entirely ignore his advice, especially with an audition looming with Larry Parnes, the most successful British rock manager of the era. Torn between following their gut and sticking with “The Beatles” or listening to the only advice they’d been given, they ended up choosing a compromise. When one of Parnes’s assistants asked for their name, they responded with “The Silver Beetles,” leaving the “Long John” behind.

The audition that day aimed to find a backing band for Liverpool’s most successful rock ‘n’ roll star, Billy Fury. Although Larry Parnes didn’t see The Silver Beetles as a fit for backing Fury, he recognised potential in several groups. Reports from some newspapers suggested that Parnes ultimately chose Cass and the Casanovas for the role, although definitive evidence of this arrangement remains elusive. Despite not landing the gig with Fury, Parnes saw enough promise in The Silver Beetles to offer them a two-week tour of Scotland, serving as the backing band for his latest rising star, Johnny Gentle.

In the end, the name change became almost incidental, as the tour with Johnny Gentle was billed simply as “Johnny Gentle and his band.” However, Cas’s suggestions weren’t completely lost on the billing. When the band hit the road, each member adopted a stage name for the shows, and “Long John” made a surprising reappearance.

The tour, which took place in May, proved to be a mixed bag for the band. Feeling under-rehearsed and unprepared, they struggled through the performances. To make matters worse Larry Parnes failed to pay them, leaving them strapped for cash. Their financial situation became so dire that on occasion they had to leave their hotel without paying—not out of a ‘we’re on tour, don’t you know’ kind of arrogance, but simply because they couldn’t afford to pay.

George Harrison, looking back on the Larry Parnes audition with hindsight, said “It was a bit of a shambles. Larry Parnes didn’t stand up saying that we were great or anything like that. It felt pretty dismal. But a few days later we got the call to go out with Johnny Gentle. They were probably thinking, ‘Oh well, they’re mugs. We’ll send a band that doesn’t need paying”.

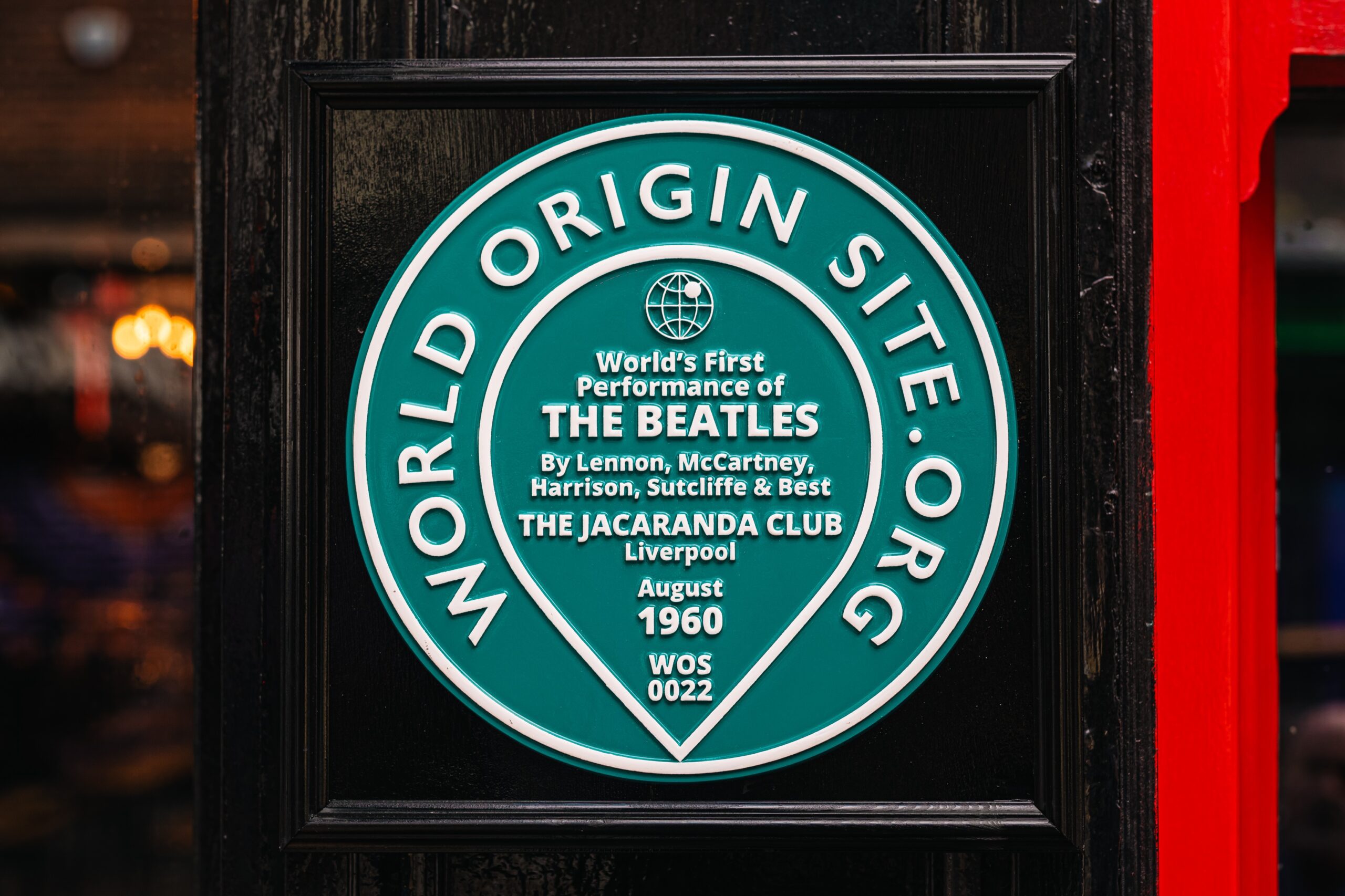

After returning to Liverpool, The Silver Beetles played their first post-tour gig at The Jacaranda on May 30th. The Jacaranda’s owner, Allan Williams, had recently started managing the band. Allan had arranged two weekly residencies for them starting in June, this time under their own name, The Silver Beetles. Both residencies took place across the Mersey on the Wirral: the first in Neston at The Institute on Thursdays, and the second at The Grosvenor Ballroom in Wallasey on Saturdays. At Neston, The Silver Beetles were replacing none other than Cass and the Casanovas, the band who had essentially given them their name.

Interestingly, despite being booked, billed, and promoted as The Silver Beetles, the band gave their name as “The Beatles” to a reporter from the Birkenhead News at a show at The Institute. This name made it to print two days later, marking the first time “The Beatles” appeared in the press. However, there’s nothing to suggest that the band had officially changed their name at this point, they continued to be billed and promoted as “The Silver Beetles” for more than ten shows after this, including a standalone performance at The Jacaranda Club the following week.

Paul McCartney, talking about returning to Liverpool after their deflating tour of Scotland, said “For a while, when we returned, we became a backing group. We were still going around as The Silver Beetles – but soon we started to drop the ‘silver’ because we didn’t really want it. John didn’t wish to be known as ‘Long John Silver’ any longer and I didn’t wish to be known as Paul Ramon.”

It isn’t clear who spoke to the reporter that day, but there’s things that would suggest it was John Lennon. John was the only member not billed under the stage name he used in Scotland and the clipping itself first came to light when John Lennon gave it to Hunter Davies, the author of the only authorised Beatles biography, during his research interviews with the band. Given we know John didn’t want to be known as Long John anymore, it makes sense that he might have dropped it at the first opportunity. If it was indeed John Lennon who provided the name, it’s possible that he was beginning to push for its use once again. After all, the previous advice to adopt a longer name had led them to a tour so “lucrative” that they ended up fleeing hotels because they couldn’t afford the bills.

After the turbulent experiences in Scotland, The Silver Beetles might have hoped for a smoother time at their upcoming residencies at The Institute in Neston and The Grosvenor Ballroom in Wallasey, yet both venues proved perhaps even more problematic. Violence marred their gigs, disrupting what should have been straightforward performances. While the band managed to complete their residency at Neston, the situation at The Grosvenor Ballroom in Wallasey was far more intense. Here, attendees from different parts of town came ready for confrontation, transforming the venue into a battleground rather than a dance hall. The escalating violence at Wallasey forced local council officials to intervene, all rock ‘n’ roll nights at the ballroom were abruptly cancelled, prematurely ending The Silver Beetles’ stint at the venue.

After their stint came to an abrupt end, The Silver Beetles embarked on a brief performance hiatus, something they wouldn’t experience again for well over a year until John and Paul went away to Paris for John’s 21st birthday. This two-week break was no holiday though; it was a crucial period of preparation and decision-making. Allan Williams had approached them with an intriguing opportunity: Bruno Koschmider, a German promoter, was in search of a five-piece Liverpool band for a residency in Hamburg. The catch? The Beatles were lacking a permanent drummer, a gap they urgently needed to fill if they were to get to Hamburg.

A panicked Stuart Sutcliffe in 1961 encapsulates how rare a break for The Beatles was: “Last night I heard that John and Paul have gone to Paris to play together – in other words, the band has broken up! It sounds mad to me, I don’t believe it.”

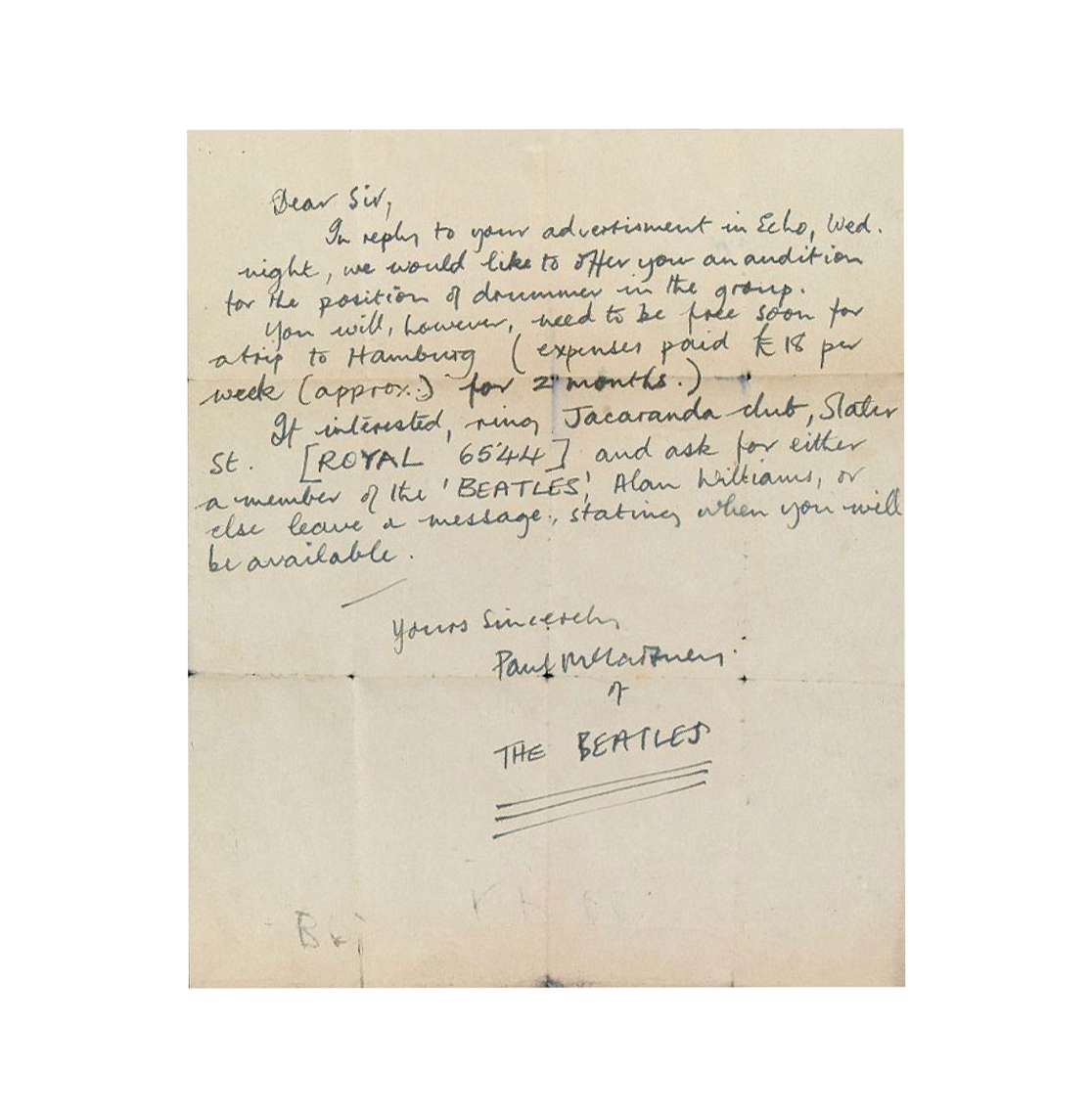

During their two-week hiatus, the band launched a search for a new drummer. They tried multiple approaches, including responding to an advertisement from a drummer seeking a band in the Liverpool ECHO. Paul McCartney took the initiative, writing a letter to the drummer and inviting him to audition. He instructed the drummer to ‘call The Jacaranda Club and ask for a member of The Beatles’. This letter, signed “Paul McCartney of The Beatles,” dated August 12th—the penultimate day of their break—is historically significant. It marks the first recorded time the band used “The Beatles” themselves, and also the first recorded time the band used it in a formal manner.

By August 12th, the band was known as The Beatles, though the exact day they changed their name from The Silver Beetles isn’t known. It probably happened during their two-week break. Considering the recent problematic bookings and the association with violence in Wallasey, it made sense to rebrand. Finding a permanent drummer and dropping “Silver” from their name—a label they never really liked anyway—were important changes as they prepared for their upcoming stint in Hamburg. This marked a new beginning, setting them up for significant opportunities ahead.

Despite Paul’s letter seeking a new drummer, George remembered someone from his past who had received a drum kit for Christmas—a chap named Pete Best. Acting swiftly, The Beatles auditioned Pete on the same day that Paul’s letter was penned and immediately offered him the job. Now, with a new name and a new drummer, they were nearly ready for Hamburg. They turned Allan Williams’ club, The Jacaranda, into their rehearsal space, but it soon evolved into something more: a live show.

Pete Best, talking about that famous night in The Jacaranda, said “The first time we played together was in The Jacaranda, downstairs. We had a couple of days; it was like a bit of a rehearsal. We played about two or three hours down there. That was the famous story where they didn’t have mic stands—the mics were attached to the end of broom handles, and as we were playing, the fans were holding them. That would be the first time that I actually played with them as a Beatle.”

As the news spread, fans converged to witness the performance. In that basement, in that moment, those present were unknowingly part of one of the most culturally impactful moments of the 20th century—and nobody, not even the band, knew it. This was the world’s first performance of a band called The Beatles.