The much-heralded 2016 Ron Howard Beatles documentary Eight Days a Week – The Touring Years chronicles the launching of the band as an international musical phenomenon and includes a little-known and unexplored sidelight into when the group confronted Black-White race relations in the U.S. in the turbulent 1960s at the Gator Bowl in Jacksonville, FL.

Dr. Kitty Oliver at the premiere for Eight Days a Week – The Touring Years in 2016.

I was there and I got to share the story of how paths can cross serendipitously and how histories can converge.

As I point out in the film, growing up in Jim Crow segregation, my contact with Whites was limited to the occasional insurance agent selling policies in the neighbourhood. Public accommodations were separate, inequities were rampant, and opportunities were stifled. As tensions accelerated, our churches warned us not to get involved in civil rights activities for fear of reprisal against our parents. Still, some of us risked rebellion. At night, for fun, I listened to the “White radio station” instead of just R&B.

That’s where I was introduced to The Beatles. They were rebels, flaunting their difference in the way they looked and sounded, and I was a fan from the start.

The Beatles arrive at JFK Airport in 1964.

As a girl of 15 or 16, I embarked on the journey with them, following the news of their first arrival in the U.S., watching their first appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show on our black and white TV, and sitting through A Hard Day’s Night in the segregated Black movie theatre seven times (for one ticket you could watch several showings all day long) – even memorizing the lines.

In our all-Black neighbourhood my best friend and I didn’t have much of a social circle in public school. But, we spent hours in self-imposed isolation in the sanctity of the music room of her parents split level house singing along to ‘Can’t Buy Me Love’; dancing to ‘Love Me Do’; fantasizing to ‘This Boy’. We debated favourites – hers was Paul. Mine was Ringo. So, when I heard the announcement on the radio that The Beatles were coming to the Gator Bowl I wanted to see them, and I decided I would go.

The concert was originally to have been racially segregated, but The Beatles refused to perform until they received an assurance from the promoter that the audience would be mixed.

We never play to segregated audiences and we aren’t going to start now. I’d sooner lose out appearance money.

– John Lennon

At the time, I didn’t know anything about the group’s press conference announcement refusing to perform for an audience where Black patrons would be forcibly segregated from Whites, probably relegated to the worse seats farthest away from the stage and maybe subjected to a threatening atmosphere if they showed up.

Dr. Kitty Oliver as a teenager in the 1960s.

I got a weekend job as a house cleaner and squirreled away almost enough money to buy a front row seat, but my financially-strapped mother kept raiding my savings until I had to settle for sitting a little further back.

On the day of the concert I took a Black-owned taxi cab to the Gator Bowl, slapped down my money on the counter of the booth outside, and headed into my first music concert. The room chilled as I walked into a sea of White faces. I sat in silence with elbows drawn in tight to make sure I did not accidentally brush an arm and spark an outburst. As the band entered and the crowd rose, a tall, slender White man to my left who looked to be in his 20’s rocked unexpectedly close as the crowd rose, thunderous, in unison, when the Beatles took the stage. Then, tunnel vision set in: Eyes glued to the front, I sang along to “She loves me, yeah, yeah, yeah…” full-voiced, just as loudly as everyone, all of us lost in the sound.

Afterwards, inching out of the stadium, I brushed past two other Black concertgoers – a brother and sister who introduced themselves and expressed surprise that I was there alone. We never know where our choices will lead. The next year, I entered an all-White university and then moved into an integrated world working as a writer and, later, doing race and ethnic relations work.

Recently, I had the chance to see a [former] Beatle perform – again in Florida – for the first time since the Gator Bowl during the latest tour of Ringo Starr and his All-Star Band. I was invited backstage before the concert for a warm hug of familiarity from my favourite, some recollections, and a photo. Our intertwined histories continue.

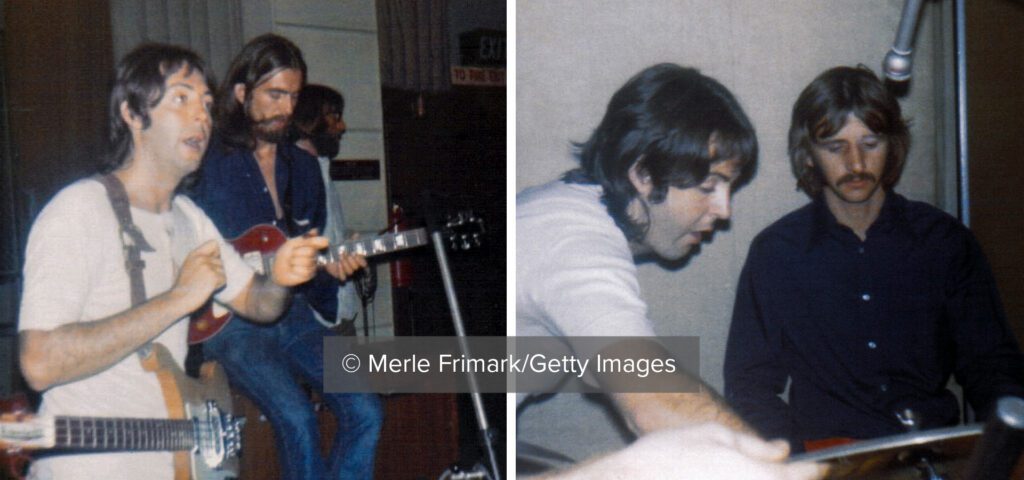

Dr. Kitty Oliver and Ringo Starr.

Afterwards, ticket in hand, I found my seat in the intimate Fort Lauderdale theatre built around the same time that the Beatles stopped touring. Onstage, the band blasted classic rock against a celestial backdrop. I was alone – again – and one of only two of three Black faces in the room.

But, as I rose to my feet with the crowd and Ringos signature Beatles songs brought back memories, I could see just how far we had come. I sang along loudly to “Boys” with another disparate crowd of grandparents, younger people, and their kids, brought together by Beatles music once again.

– Dr. Kitty Oliver

Dr. Kitty Oliver is a U.S. author, TV and radio producer, scholar and oral historian on Race and Change experiences internationally.